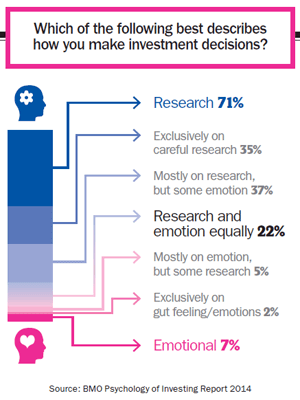

What’s the biggest threat to your portfolio? Most people would say low interest rates, high investment fees, looming inflation or the threat of a global crisis like the one that nearly brought down the financial system in 2008. But in the words of the legendary Benjamin Graham, “The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.”

Don’t take that personally. Humans simply aren’t programmed to be rational, disciplined investors. We all have what psychologists call “cognitive biases,” or mental blind spots that interfere with good decisions. We also have to fight against emotions that make it difficult to stick to a long-term strategy.

Mastering your behaviour can have a dramatic impact on your investing performance—but it won’t be easy. “Not many people are emotionally detached from their money,” says Edwin Weinstein, a psychologist and president of The Brondesbury Group, a Toronto-based research firm specializing in financial services. “We’re certainly capable of learning to do better, though sometimes it’s only after being burned.” Weinstein says investors should recognize which biases they’re most prone to and use a strategy that suits their temperament. “The first principle is know yourself and work with that.” So let’s look at the most common behavioural biases and consider ways you can overcome them.

What’s the biggest threat to your portfolio? Most people would say low interest rates, high investment fees, looming inflation or the threat of a global crisis like the one that nearly brought down the financial system in 2008. But in the words of the legendary Benjamin Graham, “The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.”

Don’t take that personally. Humans simply aren’t programmed to be rational, disciplined investors. We all have what psychologists call “cognitive biases,” or mental blind spots that interfere with good decisions. We also have to fight against emotions that make it difficult to stick to a long-term strategy.

Mastering your behaviour can have a dramatic impact on your investing performance—but it won’t be easy. “Not many people are emotionally detached from their money,” says Edwin Weinstein, a psychologist and president of The Brondesbury Group, a Toronto-based research firm specializing in financial services. “We’re certainly capable of learning to do better, though sometimes it’s only after being burned.” Weinstein says investors should recognize which biases they’re most prone to and use a strategy that suits their temperament. “The first principle is know yourself and work with that.” So let’s look at the most common behavioural biases and consider ways you can overcome them.

Overconfidence

Everyone has heard about studies revealing we all think we’re above-average drivers, with high intelligence and a keen sense of humour. Humans are hard-wired to see themselves in the most favourable terms.

“In my view, the investor’s biggest problem is overconfidence,” says Weinstein. His favourite example comes from a study he did for the Ontario Securities Commission, in which he asked investors whether they knew the meaning of several financial terms. “I gave four things that were real and one that I made up,” Weinstein recalls with a laugh. A significant minority confidently claimed they knew what the “standardized cost return index” was, and said “reciprocity fees” were an important consideration when choosing a mutual fund, even though both terms are meaningless. Weinstein says those most likely to be overconfident are “well-educated men, aged 35 to 45, and high-income earners.”

Overconfidence is rampant among individual investors and professional money managers alike. There is overwhelming evidence that beating the market over the long term is extraordinarily difficult. Even so, almost all stock pickers and mutual fund managers believe they are among the tiny number who will pull this off. When they succeed, they tend to credit their exceptional skill, even if they’re just rowing a boat during high tide. “Thinking you’re a great investor during a market upturn always has a way of correcting itself,” Weinstein says.

One way to rein in your overconfidence is to benchmark your returns against an index fund in the same asset class. If your U.S. stocks netted a 35% gain in 2013, for example, you may be humbled to learn you lagged the Vanguard S&P 500 Index ETF (VFV) by five percentage points.

Analysis paralysis

The server at a fine restaurant hands you a dessert menu with three choices: cherry cheesecake, chocolate mousse or crème brûlée. They all sound delicious, but chances are you’ll have little trouble making a selection. Now imagine the menu lists 150 mouth-watering options. Suddenly your simple choice has turned into “a kind of misery-inducing tyranny,” in the words of Barry Schwartz, author of The Paradox of Choice. No matter which treat you choose, you’ll be left wondering whether one of the other 149 choices would have been better. You may even decide to skip dessert altogether because, as Schwartz writes, “unconstrained freedom leads to paralysis.”

We all love choices. But whether it’s desserts or mutual funds, a huge number of options often leads to worse decisions and lower satisfaction. In one study commissioned by the investment firm Vanguard, researchers found 75% of employees enrolled in their workplace retirement plans when they had just four funds to choose from, but only 60% did so when they had 59 options. Many employees who were overwhelmed by choice did nothing. A host of others simply picked the most conservative choices (bond or money market funds) rather than making any attempt to learn about the funds with more potential for growth.

The psychological culprit here is called regret aversion: people tend to put off making decisions because they fear their choice will lead to a poor outcome. It often leads investors to sit on large amounts of cash, especially after they have sold at a loss. At other times it reveals itself as plain old procrastination. “Among people who are managing their own portfolios, or who are controlling the decisions of their advisers, there is a tendency to procrastinate everything from making monthly contributions to rebalancing properly,” says Keith Matthews, portfolio manager at Tulett, Matthews & Associates in Montreal and author of The Empowered Investor.

You can overcome analysis paralysis by automating many decisions: setting up preauthorized monthly contributions is an ideal way to avoid the stress of investing lump sums. For very large amounts (such as the proceeds from selling a business) Matthews sometimes eases into the market to reduce the risk of bad timing, but he’ll do so over just nine to 12 months. “Think about making a few big steps,” he says, “because if you’re doing a lot of little steps, somewhere along the way something is going to spook you and you’re going to stop.”

We all love choices. But whether it’s desserts or mutual funds, a huge number of options often leads to worse decisions and lower satisfaction. In one study commissioned by the investment firm Vanguard, researchers found 75% of employees enrolled in their workplace retirement plans when they had just four funds to choose from, but only 60% did so when they had 59 options. Many employees who were overwhelmed by choice did nothing. A host of others simply picked the most conservative choices (bond or money market funds) rather than making any attempt to learn about the funds with more potential for growth.

The psychological culprit here is called regret aversion: people tend to put off making decisions because they fear their choice will lead to a poor outcome. It often leads investors to sit on large amounts of cash, especially after they have sold at a loss. At other times it reveals itself as plain old procrastination. “Among people who are managing their own portfolios, or who are controlling the decisions of their advisers, there is a tendency to procrastinate everything from making monthly contributions to rebalancing properly,” says Keith Matthews, portfolio manager at Tulett, Matthews & Associates in Montreal and author of The Empowered Investor.

You can overcome analysis paralysis by automating many decisions: setting up preauthorized monthly contributions is an ideal way to avoid the stress of investing lump sums. For very large amounts (such as the proceeds from selling a business) Matthews sometimes eases into the market to reduce the risk of bad timing, but he’ll do so over just nine to 12 months. “Think about making a few big steps,” he says, “because if you’re doing a lot of little steps, somewhere along the way something is going to spook you and you’re going to stop.”

Framing

I recently spoke with an investor I’ll call Monique who was upset that her adviser had bought two speculative mining stocks that had since lost half their value. I asked why she didn’t just dump them, especially since she was a conservative investor who felt they were completely inappropriate. “Because I want to wait for them to get back to even before I sell,” she said. I then asked her whether she’d expect to double her money if she bought more shares. She thought I was crazy.

My chat with Monique provided a classic example of what psychologists call framing. When the same choice is presented in different ways, people often make opposite decisions. Monique framed her decision like this: “Should I sell my stocks with a huge loss or wait for them to fully recover?” When phrased like that, the decision to hold on sounds appealing. In contrast, my suggestion made me sound like a reckless gambler. But if Monique expected her stocks to get “back to even” after being cut in half, she was banking on a 100% return. The questions are the same: the only difference is how they’re framed.

Understanding the framing effect is also important when you’re investing a large lump sum. Imagine you received a $100,000 cash inheritance and are nervous about investing it because you feel stocks are overvalued and bonds will suffer if interest rates rise. Would you invest the whole amount immediately or ease into the market a little at a time? Now flip the question around and imagine you instead inherited a $100,000 portfolio of stocks and bonds. Would you immediately sell everything and reinvest the proceeds gradually? Ignoring taxes and transactions costs, this is the same decision framed in two different ways, yet most people would likely answer yes to the first and no to the second.

Edwin Weinstein encourages investors to be aware of how advisers and fund companies use framing. For example, using percentages rather than dollar amounts can change your perception of cost. “If your broker is getting a trailing commission of 1% on your mutual funds, it doesn’t sound like much. But if you have a $200,000 portfolio and instead say your broker is getting $2,000 a year, there’s a big difference.” Advisers should also use dollar amounts when assessing client risk tolerance: “Would you be comfortable if your portfolio declined by 20%?” has less impact than, “How would you feel if you lost $40,000?”

Mental accounting

When I was a teenager I found a $20 bill in the street. I was just steps away from a music store and I immediately blew the money on a couple of albums. Had I earned that $20 at my part-time job, I never would have spent it so thoughtlessly. I’d fallen prey to a cognitive bias called mental accounting, which causes us to treat money differently depending on its source.

An old story illustrates the appeal of mental accounting. A man goes to Vegas and finds a $5 casino chip in his hotel room. He heads for the roulette table and has an incredible streak of luck, amassing a pile of chips worth $1 million. Soon his luck runs out and he loses everything. When his wife asks how he did at the casino, he responds, “Not bad. I only lost $5.”

Investors use this same faulty logic: if they buy a stock for $10,000 and it rises to $15,000, they treat the original capital and the $5,000 gain differently. If the stock goes to zero, they think they’ve lost $10,000 rather than $15,000. But the value of an investment is what you would receive if you sold it today, not what you paid for it.

Mental accounting makes it easier to charge that $150 pair of shoes to your credit card than to part with $150 cash, although the cost is identical. (Indeed, if you don’t pay off your card balance every month, charging the purchase is far more expensive.) This bias also causes people to save money while also carrying large debts. You should keep cash on hand for emergencies, but it doesn’t make sense to keep a large sum in low-interest savings accounts if you’re also carrying a balance on a line of credit.

But you can use mental accounting to your advantage. Say you receive $500 a month to rent out your basement: you can earmark it for regular RRSP contributions.Or you could use your Child Tax Benefit to fund an RESP for your child. Sure, you could also make these contributions from regular salary, but thinking of these income sources as a bonus may make saving easier.

Recency bias

How well can you handle stock market swings? Many investors are confident they can handle a portfolio of 100% equities, without bonds or cash to dampen volatility. The number of aggressive investors keeps growing, as the bull market continues and memories of 2008–09 gradually fade. Blame it on recency bias: the human tendency to put more emphasis on what’s just occurred while ignoring the longer term.

Recency bias leads to chasing performance. Canadians are now questioning the wisdom of overweighting domestic stocks, since Canada makes up just 4% of the global equity market. Funny how this idea became prominent after we lagged U.S. and global markets for three years: you rarely heard it in the mid-2000s, when Canada was among the best performers in the world. “You also heard that argument in the late 1990s, after the U.S. market had done really well for a decade,” says Keith Matthews. “Investors look at what did well recently and think they have to overweight that asset class for the next several years.”

A better approach is to set a long-term target asset mix: a balanced portfolio might include equal amounts of bonds, Canadian stocks and foreign stocks. Every year, you rebalance the portfolio to get back to those targets. That way you buy what’s recently fallen in value (so should have higher expected returns in the long run) rather than chasing last year’s winners. If you find rebalancing emotionally hard, consider a low-cost balanced fund that does it for you.

Another way to fight recency bias is to think of your portfolio as a pension fund. If you’re a decade or more from retirement, your liabilities extend far into the future, so you don’t need to be obsessed with recent performance. “One role an adviser can play is getting people to really understand their investment horizon,” Matthews says. “I often see people who are 50 or 55 and planning to retire at 60, and they think their investment horizon is five or 10 years. But really it might be 20, 25 or 30 years.” That’s because your horizon stretches well past your retirement date: your portfolio needs to last your whole life—longer if you want to leave something to your heirs. “We refer to time horizon in just about every client meeting, because it’s important to remind people how long they have to invest.”

Illusion of control

In a series of famous experiments beginning in the 1970s, psychologist Ellen Langer showed that people often believe they have control over certain random events. For example, craps players tend to throw the dice harder if they want higher numbers, and softly if they want lower numbers. This illusion of control helps explain why people who buy lottery tickets are given an option to choose their own numbers, even though all combinations have the same (and staggeringly low) chance of winning the jackpot. Indeed, in one of Langer’s experiments, people who chose their own lottery numbers were more reluctant to trade their tickets than those whose numbers had been assigned randomly.

Investors have a terrible time accepting randomness and ambiguity. Presented with a series of facts, most of us cannot resist the impulse to create stories and explanations, because this helps us feel we’re in control. No one can consistently predict economic growth, the performance of stock markets, direction of interest rates, or the movement of currencies. Even after the fact, we usually can’t pinpoint why stocks went up or down: markets are extraordinarily complex and cause-and-effect relationships are never simple. But this truth is too painful to acknowledge, so our brains look for something more comforting.

If you follow the markets daily you’ve probably seen statements like this actual example from a national newspaper: “U.S. stock index futures were under pressure on Friday, weighed by bearish concern over Spain’s rising borrowing costs and Chinese economic data.” Does anyone really believe the daily movements of the U.S. stock market can be explained by factors like Spanish interest rates or Chinese GDP reports? The point is we want to believe this, because a tidy narrative is more satisfying than admitting these daily moves are unpredictable.

Long-term investors need to accept that randomness and uncertainty are part of the deal. But that doesn’t mean you have no influence over other parts of your investment experience: you can’t control your returns but you have the power to determine your savings rate, the number of years you invest, your asset mix, your costs and (to some extent) your taxes.

Action bias

When you’re stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic, do you constantly move from one lane to the other? More than a decade ago, an Ontario researcher, Donald Redelmeier, led a study that concluded drivers routinely believe changing lanes helped them move faster even when all the lanes have the same average speed. In another study on soccer penalty kicks, researchers found goalkeepers dive either left or right on 94% of penalty kicks, even though they would stop more shots if they simply stood still.

These are examples of action bias: the tendency to resist doing nothing, even if an action is counterproductive. This bias is behind much of the criticism of buy-and-hold investors, especially by advisers who believe they can make tactical moves—overweighting asset classes or sectors based on current market conditions—to improve returns. It’s especially acute during periods of economic turmoil: investors who stay the course are mocked for fiddling while Rome burns, yet they usually outperform in the long run. As the psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman writes in Thinking, Fast and Slow: “It’s clear that for the large majority of individual investors, taking a shower and doing nothing would have been a better policy than implementing the ideas that came to their minds.”

To be clear, “doing nothing” in this context doesn’t imply you should give no thought to what’s in your portfolio or how it is performing. It’s more helpful to think of it as sticking with a long-term plan. “Assuming your time horizon is consistent with your investments and you have a well-thought-out portfolio,” Weinstein says, “doing nothing is often what makes sense.”

The bias to action is a big reason why so few people embrace simple solutions. Whether you’re a Couch Potato, a dividend investor, or someone who uses actively managed funds, your strategy doesn’t need to be complicated, and much of the time you’re best just leaving it alone. Yet few can resist tinkering with their portfolios.

The good news, says Keith Matthews, is many investors eventually realize the peace that comes with a consistent approach. “What I am now seeing is not resistance to simple solutions: I’m actually seeing relief. People say, ‘This is amazing: I get a better portfolio and I simplify my life.’ If you take the time to explain the facts, more often than not investors become aware of the elegance of simple ideas.”

What’s the biggest threat to your portfolio? Most people would say low interest rates, high investment fees, looming inflation or the threat of a global crisis like the one that nearly brought down the financial system in 2008. But in the words of the legendary Benjamin Graham, “The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.”

Don’t take that personally. Humans simply aren’t programmed to be rational, disciplined investors. We all have what psychologists call “cognitive biases,” or mental blind spots that interfere with good decisions. We also have to fight against emotions that make it difficult to stick to a long-term strategy.

Mastering your behaviour can have a dramatic impact on your investing performance—but it won’t be easy. “Not many people are emotionally detached from their money,” says Edwin Weinstein, a psychologist and president of The Brondesbury Group, a Toronto-based research firm specializing in financial services. “We’re certainly capable of learning to do better, though sometimes it’s only after being burned.” Weinstein says investors should recognize which biases they’re most prone to and use a strategy that suits their temperament. “The first principle is know yourself and work with that.” So let’s look at the most common behavioural biases and consider ways you can overcome them.

What’s the biggest threat to your portfolio? Most people would say low interest rates, high investment fees, looming inflation or the threat of a global crisis like the one that nearly brought down the financial system in 2008. But in the words of the legendary Benjamin Graham, “The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.”

Don’t take that personally. Humans simply aren’t programmed to be rational, disciplined investors. We all have what psychologists call “cognitive biases,” or mental blind spots that interfere with good decisions. We also have to fight against emotions that make it difficult to stick to a long-term strategy.

Mastering your behaviour can have a dramatic impact on your investing performance—but it won’t be easy. “Not many people are emotionally detached from their money,” says Edwin Weinstein, a psychologist and president of The Brondesbury Group, a Toronto-based research firm specializing in financial services. “We’re certainly capable of learning to do better, though sometimes it’s only after being burned.” Weinstein says investors should recognize which biases they’re most prone to and use a strategy that suits their temperament. “The first principle is know yourself and work with that.” So let’s look at the most common behavioural biases and consider ways you can overcome them.

We all love choices. But whether it’s desserts or mutual funds, a huge number of options often leads to worse decisions and lower satisfaction. In one study commissioned by the investment firm Vanguard, researchers found 75% of employees enrolled in their workplace retirement plans when they had just four funds to choose from, but only 60% did so when they had 59 options. Many employees who were overwhelmed by choice did nothing. A host of others simply picked the most conservative choices (bond or money market funds) rather than making any attempt to learn about the funds with more potential for growth.

The psychological culprit here is called regret aversion: people tend to put off making decisions because they fear their choice will lead to a poor outcome. It often leads investors to sit on large amounts of cash, especially after they have sold at a loss. At other times it reveals itself as plain old procrastination. “Among people who are managing their own portfolios, or who are controlling the decisions of their advisers, there is a tendency to procrastinate everything from making monthly contributions to rebalancing properly,” says Keith Matthews, portfolio manager at Tulett, Matthews & Associates in Montreal and author of The Empowered Investor.

You can overcome analysis paralysis by automating many decisions: setting up preauthorized monthly contributions is an ideal way to avoid the stress of investing lump sums. For very large amounts (such as the proceeds from selling a business) Matthews sometimes eases into the market to reduce the risk of bad timing, but he’ll do so over just nine to 12 months. “Think about making a few big steps,” he says, “because if you’re doing a lot of little steps, somewhere along the way something is going to spook you and you’re going to stop.”

We all love choices. But whether it’s desserts or mutual funds, a huge number of options often leads to worse decisions and lower satisfaction. In one study commissioned by the investment firm Vanguard, researchers found 75% of employees enrolled in their workplace retirement plans when they had just four funds to choose from, but only 60% did so when they had 59 options. Many employees who were overwhelmed by choice did nothing. A host of others simply picked the most conservative choices (bond or money market funds) rather than making any attempt to learn about the funds with more potential for growth.

The psychological culprit here is called regret aversion: people tend to put off making decisions because they fear their choice will lead to a poor outcome. It often leads investors to sit on large amounts of cash, especially after they have sold at a loss. At other times it reveals itself as plain old procrastination. “Among people who are managing their own portfolios, or who are controlling the decisions of their advisers, there is a tendency to procrastinate everything from making monthly contributions to rebalancing properly,” says Keith Matthews, portfolio manager at Tulett, Matthews & Associates in Montreal and author of The Empowered Investor.

You can overcome analysis paralysis by automating many decisions: setting up preauthorized monthly contributions is an ideal way to avoid the stress of investing lump sums. For very large amounts (such as the proceeds from selling a business) Matthews sometimes eases into the market to reduce the risk of bad timing, but he’ll do so over just nine to 12 months. “Think about making a few big steps,” he says, “because if you’re doing a lot of little steps, somewhere along the way something is going to spook you and you’re going to stop.”