A practical guide to Canadian REIT investing in 2025

From passive index funds to active managers and DIY portfolios, here’s how to approach Canadian REIT investing in today’s market.

Advertisement

From passive index funds to active managers and DIY portfolios, here’s how to approach Canadian REIT investing in today’s market.

North American markets appear to have entered another “Roaring Twenties.” But unlike the last century’s version, the current “everything bubble” is driven by speculative valuations in anything related to artificial intelligence or quantum computing. Many of these companies trade at sky-high multiples of revenue—or in some cases, have no earnings at all.

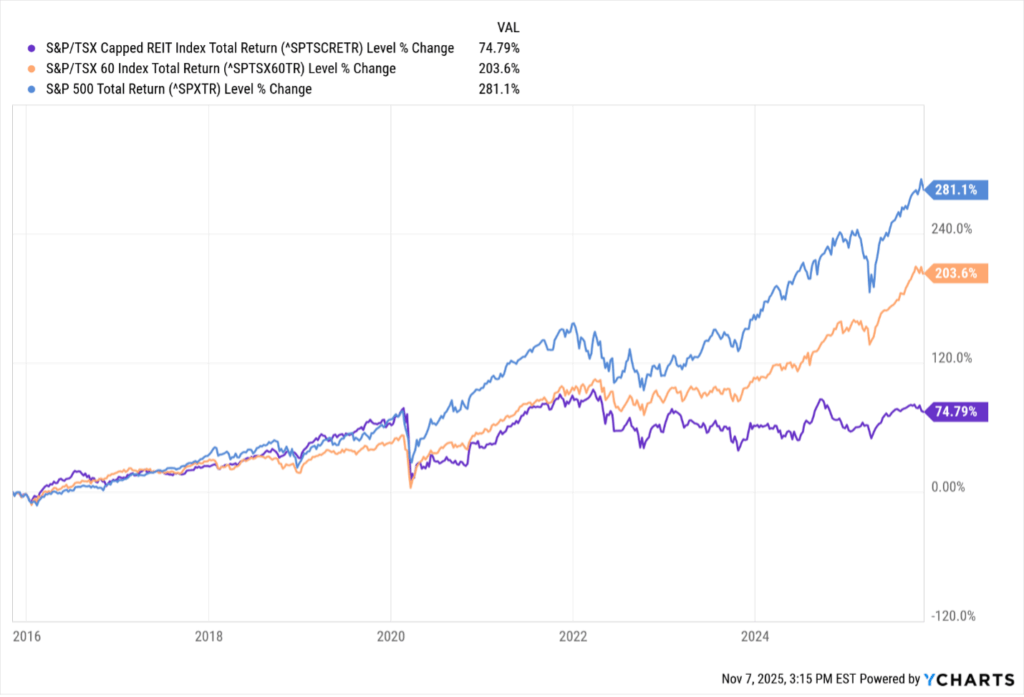

The chart below compares total returns, which measure both price appreciation and reinvested dividends, across major Canadian and U.S. equity benchmarks since 2016.

While the S&P 500 and S&P/TSX 60 have surged higher, Canadian real estate investment trusts (REITs) have badly lagged. The gap hasn’t narrowed meaningfully either. Even with distributions reinvested, the S&P/TSX Capped REIT Index remains well below its pre-COVID highs, with little evidence of a sustained rebound.

I’m not a value investor by nature, nor a sector picker, but divergences like this give me pause. Canadian REITs may quietly represent one of the few asset classes that aren’t overvalued today—and could offer genuine recovery potential in the years ahead, especially as interest rates fall.

The irony is that many Canadians still see real estate as the path to financial independence after decades of soaring home prices, even with the recent downturn in major cities like Toronto. Yet few consider REITs, which do the same thing at scale, with diversification and liquidity that private property ownership can’t match, especially when packaged into an exchange-traded fund (ETF).

REITs have their own nuances that make them very different from regular stocks. You can’t analyze them using the same metrics you’d apply to a company like Dollarama. That’s because REITs are pass-through vehicles: they’re exempt from paying corporate income tax as long as they distribute most of their taxable income to unitholders.

Unlike operating companies that make money by selling products or services, REITs earn revenue primarily from rent. They own portfolios of income-producing real estate and pass that rental income on to investors through distributions, which are usually paid monthly and tend to be higher than the average dividend yield from stocks in other sectors.

Canadian REITs span a variety of sub-sectors, including:

Because of how REITs operate, you can’t value them using conventional measures like earnings per share (EPS) or price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios. In fact, those figures can be misleading on sites like Yahoo Finance or Google Finance. That’s because REITs use significant non-cash charges such as depreciation, which can artificially depress reported earnings even when cash flow is strong.

The key metric for REITs is funds from operations (FFO). FFO adjusts net income by adding back depreciation and amortization (which are non-cash expenses) and subtracting any gains or losses from property sales. In simple terms, FFO is a more accurate measure of a REIT’s true cash-generating ability.

Once you know the FFO, you can calculate price-to-FFO, the REIT equivalent of a price-to-earnings ratio. It tells you how expensive a REIT is relative to its cash flow. Comparing a REIT’s price-to-FFO to its own historical average and to peers within the same subsector (e.g., residential vs. residential) gives a much fairer sense of value.

FFO is also used to judge whether a REIT’s distribution is sustainable. Since REITs pay out most of their income, the payout ratio is typically based on the percentage of FFO, not earnings. A lower payout ratio suggests more cushion to maintain distributions through economic downturns.

Supporting FFO is the occupancy rate, which measures how much of a REIT’s property portfolio is currently leased. It’s usually reported quarterly and varies by sector. As of late 2025, occupancy remains strongest in residential REITs, driven by housing demand, while office REITs continue to face pressure from remote work trends. Generally, you want to see occupancy of 95% or higher.

Another useful valuation tool is net asset value (NAV) per unit, which estimates the fair value of a REIT’s underlying real estate after liabilities. NAV divides the total appraised property value minus debt by the number of outstanding share units. The market price of a REIT can trade at a premium or discount to NAV—there’s no guarantee it will converge—but it’s still a good reality check for whether a REIT looks undervalued.

The best place to find these figures is in a REIT’s quarterly reports and audited financial filings. Some data providers, like ALREITs, compile these metrics for most Canadian-listed REITs.

Personally, I prefer REIT ETFs over picking individual REITs. Valuing REITs properly requires a working knowledge of specialized metrics. And while each REIT is diversified internally, most still focus on one property type or region. A REIT ETF spreads that exposure across multiple sectors and issuers, averaging out risks and simplifying portfolio management.

In Canada, REIT ETFs generally fall into two camps: passive index trackers and actively managed funds. Each has its strengths, and I’ll walk through some of the more notable examples in both categories, along with their pros and cons.

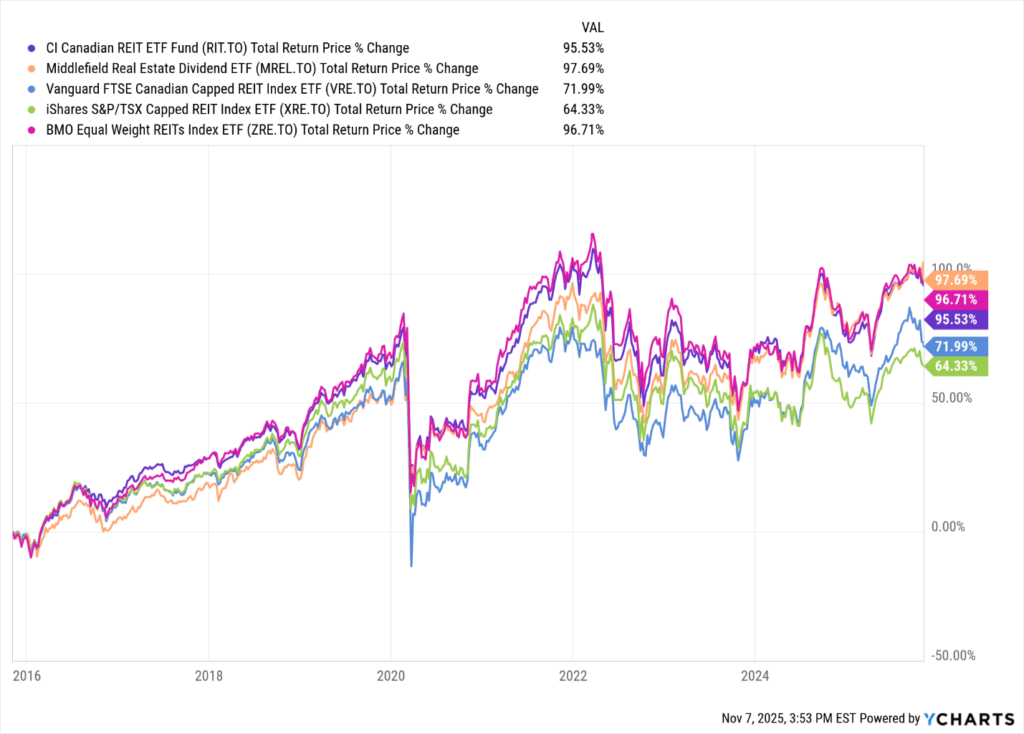

The passive Canadian REIT ETF market is dominated by the big three issuers—Vanguard, iShares Canada, and BMO Global Asset Management—but all three options come with some meaningful trade-offs despite their scale.

The largest fund in the category by assets under management is the iShares S&P/TSX Capped REIT Index ETF (XRE). It tracks the S&P/TSX Capped REIT Index and has been a staple in the market since 2002, helped by strong brand recognition and a 3.56% 12-month trailing yield paid monthly.

In spite of these attributes, I’m not a fan. The index only holds 16 names, and because it’s market-cap weighted, larger REITs like CAPREIT and RioCan together make up about 23% of the portfolio. That concentration is a recurring issue with many Canadian sector indices. The management expense ratio (MER) is also steep—0.6% for what’s ultimately a simple portfolio you could replicate yourself using a zero-commission brokerage.

The Vanguard FTSE Canadian Capped REIT Index ETF (VRE) is more reasonable on costs with a 0.39% MER, but the yield is underwhelming at 2.44%. The reason is that its benchmark—the FTSE Canada All Cap Real Estate Capped 25% Index—isn’t a pure REIT index. It includes real estate operating companies like FirstService and Colliers that don’t actually own properties. These firms earn management and service fees rather than rental income, so they pay much lower distributions. In my view, that defeats the purpose of holding a REIT ETF in the first place.

If you’re going to stick with a passive approach, my preferred pick is the BMO Equal Weight REITs Index ETF (ZRE). It tracks the Solactive Equal Weight Canada REIT Index, holding 20 REITs with equal weighting. This structure naturally rebalances over time—selling relative winners and buying laggards—which helps manage concentration risk.

The 4.96% yield is decent, though it does come with the highest MER at 0.61%. Even so, I think ZRE currently strikes the best balance between diversification, income, and methodology among Canada’s passive REIT ETFs.

The already high costs and structural limits of Canadian REIT index ETFs are why I think a few lesser-known active REIT ETFs deserve a closer look. In this case, active management might actually have the upper hand.

The Middlefield Real Estate Dividend ETF (MREL) is a good example. It takes a bottom-up, active approach and isn’t confined strictly to Canadian REITs. Currently, about 18% of its portfolio is in mostly U.S. names, giving it a bit more flexibility than a benchmark-bound index fund.

The fund’s drawback is cost—its management fee is 0.75%, but once all expenses are factored in, the latest MER climbs to 1.21%. You’ll only find that if you dig into the ETF facts sheet. In return, though, investors get a hefty 7.16% yield paid monthly.

A cheaper alternative is the CI Canadian REIT ETF (RIT) with a 0.87% MER. It also has the option to allocate up to 30% of assets outside its benchmark. RIT has been around since 2004, giving it one of the longest active track records in the space, and it currently pays a 4.86% yield.

Both funds also share a common trait typical of true active management—they’re effectively black boxes. There’s limited visibility into how managers select and weight securities beyond the high-level details disclosed publicly.

If you choose to invest, make a point of reading their quarterly fund commentaries. These updates usually highlight key contributors and hindrances to performance, recent trades, and management’s outlook for the REIT sector—all essential for understanding how your money is actually being managed.

Performance-wise, the higher fees of active management have largely paid off. Both RIT and MREL have outperformed passive funds like VRE and XRE, though not BMO’s equal-weighted ZRE.

Their ability to step outside the narrow Canadian REIT universe has been key. Some argue it’s unfair to compare funds like RIT and MREL against pure-play Canadian REIT ETFs, but that’s precisely the point—active management should use that flexibility if it helps deliver better returns. Adding a measured slice of U.S. REIT exposure isn’t a departure from mandate; it’s a way to diversify and capture opportunities.

That said, given ZRE’s disciplined, rules-based equal-weight approach and lower fees, it remains my personal favorite heading into the new year. In a concentrated sector like Canadian REITs, equal weighting often strikes the best balance between cost, diversification, and performance consistency.

Another option is to skip ETFs altogether and build your own REIT basket. With the rise of commission-free brokerages like Wealthsimple and Questrade, that’s now easier and more cost-effective than ever — especially given how small and concentrated the Canadian REIT space already is.

If you go this route, a few common-sense rules can go a long way. First, keep your REIT allocation to a reasonable percentage of your overall portfolio and watch for overlap with any Canadian equity ETFs you already hold.

Second, prioritize quality first. Look for REITs with consistent FFO growth, solid distribution coverage, high occupancy rates, and manageable debt-to-asset ratios. Moreover, diversify your holdings across residential, industrial, office, and retail REITs to reduce exposure to any single property type.

Finally, it’s best to keep REITs inside a registered account. That’s because most REIT distributions are taxed as ordinary income rather than eligible dividends, which can significantly erode returns for investors in higher income brackets.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email

Most REITS are not doing all that good for the past few years and that will likely continue. I prefer to buy the REIT stock itself instead of a ETF which holds a basket of them.