Can you hedge against a market crash with ETFs?

Short answer: yes, inverse and volatility ETFs can hedge market crashes, but the cost, complexity, and timing often outweigh the benefit for long-term investors.

Advertisement

Short answer: yes, inverse and volatility ETFs can hedge market crashes, but the cost, complexity, and timing often outweigh the benefit for long-term investors.

Earlier in August 2025, I wrote a column outlining an alternative to the classic 60/40 stock-and-bond portfolio called the 40/30/30 portfolio. The idea was simple: allocate 40% to equities, 30% to bonds, and 30% to alternative asset classes that have the potential to move differently when both stocks and bonds struggle. In theory, that mix would have helped in rare years like 2022, when equities and fixed income fell together.

That approach, however, comes with trade-offs. Higher fees are a real issue, as many alternative strategies rely on active management. Complexity is another. Finding ETFs that genuinely diversify returns rather than just repackage familiar risks is not easy. And even when you get the construction right, one major gap remains. The portfolio is not designed to protect against a true market crash. When I say crash, I mean sudden, deep, double-digit drawdowns like those seen during the 2008 financial crisis or the sudden collapse in March 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: Testfolio.io

In the sections that follow, I will walk through two ETF approaches that retail investors have access to, highlighting Canadian-listed options where available. It is worth noting up front that the Canadian market is far more limited than the U.S. in this area, but you still have a few options.

And while these strategies can offer protection in specific scenarios, there is no free lunch. As you will see, the costs, complexity, and implementation challenges often make crash-hedging ETFs difficult to use effectively, even for experienced investors.

Inverse ETFs are designed to be short-term trading tools that aim to deliver the opposite return of a benchmark over a single trading day. Most track broad market indexes, though some focus on specific sectors or even individual stocks. The key point is that their objective resets daily. They are not built to provide long-term protection.

A well-known U.S. example is the ProShares Short S&P 500 ETF (NYSEArca:SH). On any given trading day, SH targets a return equal to negative one times the daily price return of the S&P 500. If the index rises 1%, SH should fall about 1%. If the index drops 1%, SH should rise about 1%. In practice, it does a reasonable job of delivering that daily inverse exposure.

For investors seeking stronger downside protection, leveraged inverse ETFs are also available. These apply leverage to magnify the inverse relationship. An example is Direxion Daily S&P 500 Bear 3X Shares (NYSEArca:SPXS), which targets negative three times the daily return of the S&P 500. If the index falls 1% in a day, SPXS aims to rise roughly 3%. If the index rises 1%, SPXS should fall about 3%.

Canadian investors have access to similar products now. Instead of using U.S.-listed ETFs, investors can look at options such as the BetaPro -3x S&P 500 Daily Leveraged Bear Alternative ETF (TSX:SSPX).

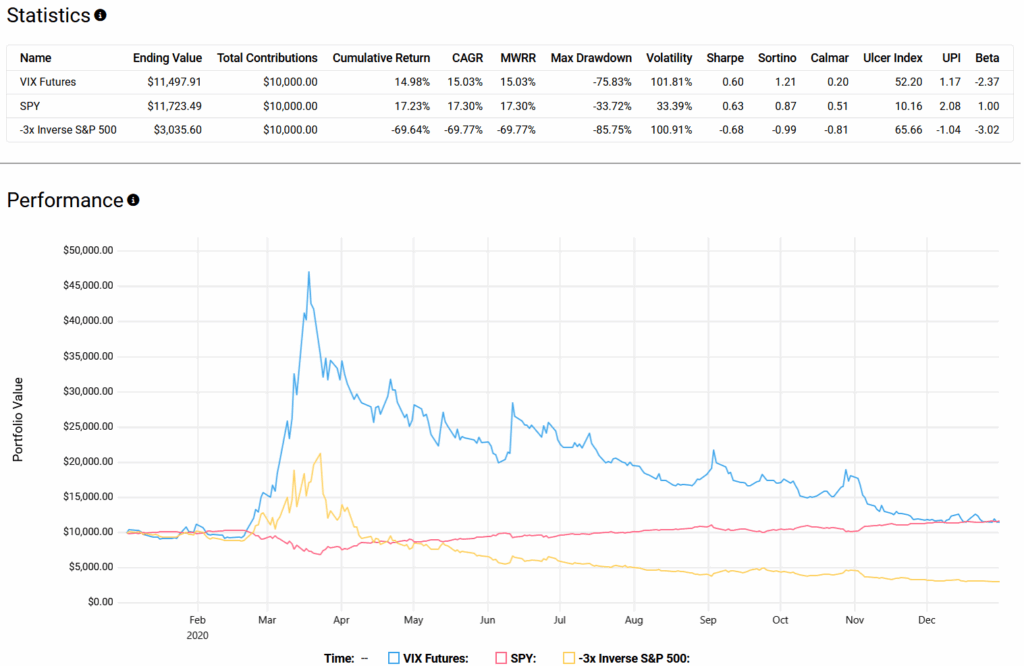

During sharp selloffs, these ETFs can do exactly what they are designed to do. During the March 2020 COVID-related market panic, as the S&P 500 plunged, inverse ETFs like SH and leveraged versions such as SPXS rose sharply, with the leveraged funds moving by a much larger magnitude.

Source: Testfolio.io

As the chart above shows, the problem with these ETFs turns up once the panic passes. As markets recovered after March 2020, both unleveraged and leveraged inverse ETFs began to fall steadily. This highlights the core limitation of these products: you cannot buy and hold inverse ETFs if you accept that, over time, equity markets tend to rise. A permanent short position against the broad U.S. stock market is structurally a losing bet, which is why issuers are careful to emphasize that these products are intended for day trading only.

That creates another challenge. Using inverse ETFs effectively requires anticipating the crash and positioning just before it happens, then exiting before the recovery begins. That is market timing, and it’s not only an active strategy; it requires being right twice. Even professional investors struggle with this consistently, and retail investors tend to fare worse.

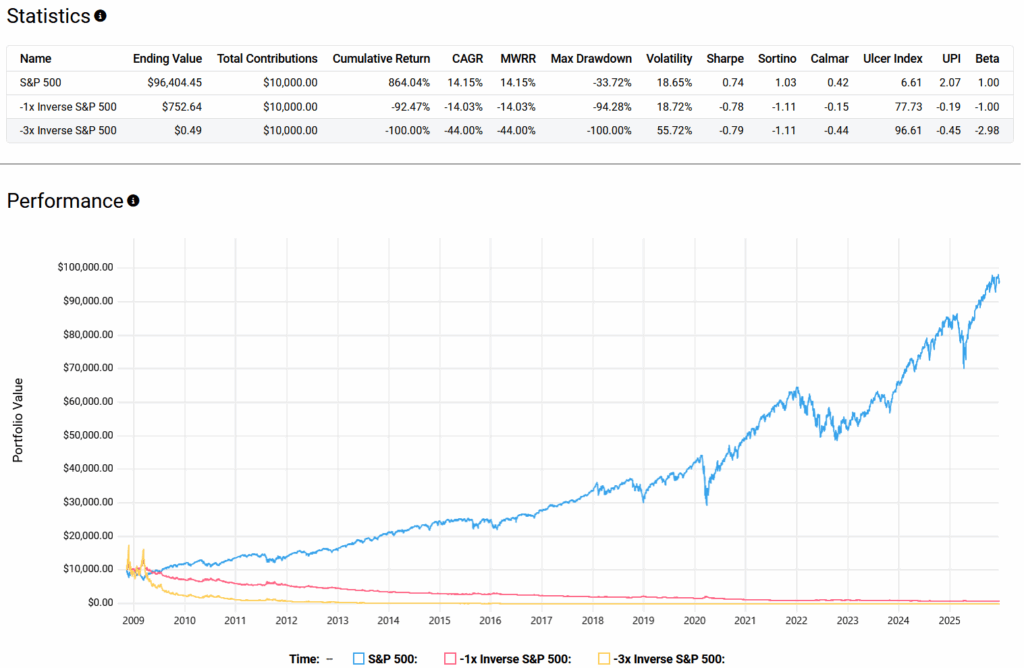

The long-term outcomes reflect those headwinds. Over a roughly 17.1-year period from November 5, 2008, to December 18, 2025, a buy-and-hold investment in inverse ETFs like SH and SPXS would have effectively gone to zero after many reverse splits.

Source: Testfolio.io

That outcome is driven by several factors. First, the underlying benchmark generally trends upward over long periods. Second, inverse ETFs carry relatively high fees, with expense ratios of 0.89% for SH and 1.02% for SPXS. Third, daily compounding works against investors in volatile markets. When prices swing up and down, the daily reset causes losses to compound faster than gains, creating volatility drag.

In short, inverse ETFs can provide short-term protection during sudden market declines, but using them as crash insurance requires precise timing. That makes them difficult to implement effectively and risky to hold for longer than a few days.

Another way investors try to hedge against market crashes is through products linked to the Cboe Volatility Index, better known as the VIX. The VIX measures the market’s expectation of near-term volatility in the S&P 500, based on prices of index options. When investors aggressively buy downside protection, option prices rise and the VIX moves higher. Because volatility tends to spike during periods of stress, the index has earned its nickname as Wall Street’s “fear gauge.”

You cannot invest directly in the VIX itself. It is a mathematical construct, not an asset. As an index, it does not own securities, generate cash flow, or trade on an exchange. To make volatility investable, exchanges list VIX futures, which are contracts that reflect expectations for where volatility will be at a specific point in the future. These futures are issued with different expiration months, such as January, February, or March of a given year.

Importantly, owning a VIX future is not the same thing as owning spot VIX exposure. If you wanted to go long volatility today, you would not be buying today’s VIX reading. You would be buying a futures contract, such as the January 2026 VIX future, which reflects the market’s expectation of volatility at that future date. Even so, the nearest-dated contract, often called the front-month future, tends to be correlated with spot VIX movements, especially during sharp market selloffs.

For this reason, some ETF issuers package this exposure into volatility ETFs, with a Canadian example being the BetaPro S&P 500 VIX Short-Term Futures ETF (TSX:VOLX). A common U.S. example is the ProShares VIX Short-Term Futures ETF (BATS:VIXY), which tracks the S&P 500 VIX Short-Term Futures Index. The fund maintains exposure to the two nearest VIX futures contracts. As of late December, that means roughly 90% in the January 2026 contract and 10% in the February 2026 contract.

During market crashes, these products can perform extremely well. In the March 2020 COVID selloff, short-term VIX futures exposure surged as volatility exploded higher. ETFs like VIXY rose sharply while the S&P 500 fell, and delivered gains that exceeded even those of a leveraged inverse ETF such as SPXS.

Source: Testfolio.io

This payoff profile is known as convexity, where small increases in market stress can lead to asymmetrical large gains. That convexity is why professional investors often use volatility futures as a tail risk hedge, meaning protection against rare, fast-moving, and severe market events.

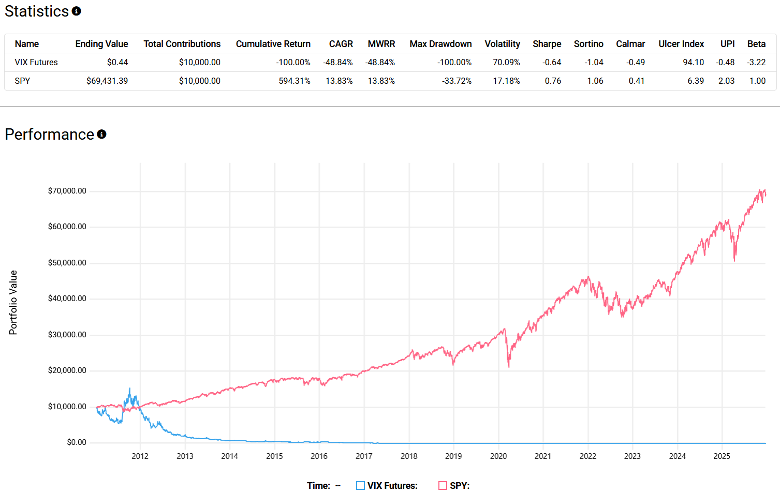

The problem is what happens outside of those moments. Like inverse ETFs, volatility ETFs have historically been poor long-term holdings. Over a roughly 15-year period from January 4, 2011, to December 18, 2025, a buy-and-hold investment in VIXY would have effectively gone to zero, requiring repeated reverse splits to keep the fund trading.

Source: Testfolio.io

The primary source of this decay lies in the structure of the VIX futures market. Most of the time, the VIX futures curve is in contango, meaning longer-dated futures trade at higher prices than near-term ones. Because ETFs like VIXY hold the nearest contract, they must roll their exposure forward each month. In a contango environment, that means selling the expiring contract at a lower price and buying the next contract at a higher price. This process creates negative roll yield, which steadily drags down returns.

There is also a structural issue with volatility itself. Unlike equities, which have a positive long-term return due to earnings growth, buybacks, and dividends, volatility is mean-reverting. Spikes tend to be sharp but short-lived, followed by long periods of decay back to historical averages. Being long volatility over time is therefore similar to paying an insurance premium continuously, with occasional large payouts that rarely offset the cumulative cost.

Layer on high fees, with VIXY charging a management expense ratio of 0.85%, and you have persistent negative carry from a combination of roll decay from contango, mean reversion, and high expenses that is difficult for investors to overcome.

As with inverse ETFs, success depends almost entirely on timing. You need to enter before volatility spikes and exit quickly once markets stabilize. That is a difficult task even for institutional investors, and it makes volatility ETFs an unreliable form of long-term crash protection for most portfolios.

The issue with inverse ETFs and VIX futures ETFs is not whether they can hedge a market crash. We know they can, and episodes like the March 2020 COVID selloff show that they can work well. The problem is integrating them into a retail investor’s portfolio in a way that is both practical and repeatable. Execution risk is the main obstacle and timing matters enormously.

Enter too early and you steadily bleed capital while waiting for a crash that may not arrive before the position has lost much of its value. Even if you manage to time the entry correctly, the next challenge is knowing when to exit. Market bottoms are only obvious in hindsight, and holding on too long as markets recover can quickly erase the gains that the hedge delivered.

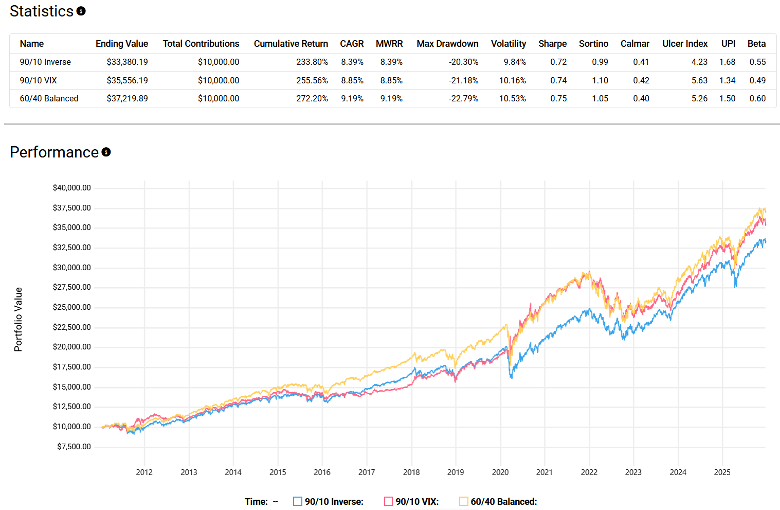

One alternative sometimes proposed is to hold a small, permanent allocation to these hedging tools. For example, instead of a traditional 60/40 stock and bond portfolio, an investor might try a 90/10 mix of stocks and VIX futures exposure, or a 90/10 allocation to stocks and a negative three times inverse equity ETF, rebalanced on a fixed quarterly schedule regardless of market conditions. In theory, this provides crash protection without the need to time entries and exits. In practice, the results are underwhelming. While such portfolios can reduce losses during extreme drawdowns, they tend to lag a traditional 60/40 mix over full cycles.

The backtest below shows lower compound returns, higher maximum drawdowns, greater annual volatility, and weaker risk-adjusted performance as measured by the Sharpe ratio when using market hedging tools. The outcome is often a slightly worse result achieved with more complexity and higher fees.

Source: Testfolio.io

That leads to the broader point: market crashes are part and parcel of investing in stocks. The equity risk premium exists precisely because investors are compensated for enduring volatility, prolonged bear markets, and occasional gut-wrenching drawdowns.

A more practical exercise is to look honestly at history. Review past drawdowns and ask whether you could tolerate watching your portfolio decline steadily for years, or lose 20% of its value in a matter of weeks. If the answer is no, the solution is usually not an exotic hedge. Traditional diversification still works. Holding high-quality bonds, allocating to assets like gold that can help resist currency debasement, or simply maintaining a cash cushion can reduce portfolio (and personal) stress without relying on precise timing.

Promises of crash protection can be tempting, but they often come at a high cost, and the burden of execution rests entirely on the investor.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email